Perhaps today’s troubles began with who signed the Declaration of Independence

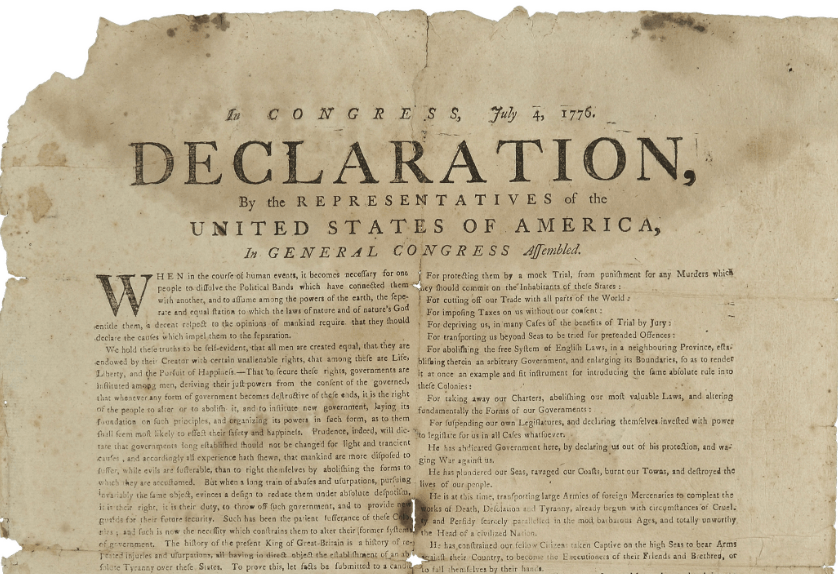

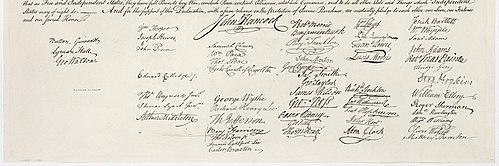

ON JULY 4, 249 YEARS AGO, 56 white men got together in the city of Brotherly Love to sign a not-so-loving letter to their absentee landlord informing him that they didn’t like the way he was running the place, so they were going co-op.

The recipient of the letter was Great Britain’s King George III. The men assembled in Philadelphia were an elite class of lawyers, doctors, merchants, and plantation owners who were aspiring to wrest control of the 13 original colonies.1 These guys were America’s first aristocracy, or what would be today’s “1 percent.”

Only two or three of the signers came from humble origins, most significantly Benjamin Franklin, who worked his way up and out of indentured servitude as a child.2

Of the signers, 45 were affluent landowners. These included Thomas Jefferson, who owned 5,000 acres and Richard Henry Lee (great-uncle of the infamous Robert E. Lee), who was the largest landowner of the group, with 20,000 acres. Most of the signers — as many as 40 — inherited their wealth.

These men, known as the Founding Fathers, represented the upper class of this era who made up 10 percent of the population but controlled between 50 to 70 percent of the land.

The prize goes to the Van Renssalaer family, which controlled 1 million acres in New York.

Of the signers, 41 were slaveholders, including Jefferson, who was at the time subjecting 600 people to captivity and forced labor while avowing equality for all. He took one of these slaves, Sally Hemmings, with him to Paris at the age of 14 and she would soon thereafter bear his child as a child herself.3

George Washington, also a plantation owner and slave-owner, didn’t sign the Declaration because he was out of town running the Revolutionary Army. Washington accepted the position as general of the colonial military at least in part because he felt snubbed by King George III. Washington believed he was deserving of a commissioned officer’s title for his role in the so-called French and Indian War.4 Said commission was never granted and the nation’s first leader bore a grudge, which is all that is needed these days for a rich white man to assume the highest office.

Washington inherited a respectable fortune of 2,500 acres and 30 or so slaves, but had a bit of an inferiority complex, which may have been part of his motivation for marrying up. Martha Washington, née Dandridge, was a widow and one of the richest individuals in Virginia. Matrimony conveniently increased Washington’s income tenfold.5

What all the complaining was about

WHAT WE REMEMBER MOST about the the 27 grievances in the Declaration of Independence is No. 17, which is etched into every American schoolchild’s skull as the catchy phrase: “No taxation without representation!”

This was certainly a concern, but paled in comparison to the charges of political oppression, military tyranny, judicial injustice, economic oppression, and willful neglect of the individual states.

It would not be difficult to match each of the 27 complaints then with similar charges lodged against the current despot ruler of the United States. Just to highlight some of the originals with their modern-day doppelgangers:

No. 9: Making judges dependent on his will alone

No. 10: Sending officers to harass civilians

No. 12: Rendering the military above civilian power

No. 14: Quartering troops among civilian populations6

No. 18: Denying trial by jury

No. 19: Abducting and shipping civilians overseas for pretended offenses

No. 27: Exciting domestic insurrection

These illustrate precisely why the Founding Fathers wrote the document in the first place and why they then undertook a multiyear battle to become independent.

A most telling omission

ANOTHER PHRASE THAT HAS BEEN indelibly pressed into the American lexicon is that “all men are created equal.” Yet, even while writing this in the Declaration’s introduction, the Founding Fathers knew it was hypocritical to exclude slavery from the narrative.

Jefferson, to his credit, did try to blame the king for America’s system of subjugation. Almost immediately, though, what would have been a 28th grievance was stricken. The south, of course, was dependent on slavery and had no economic motive to change their business model. Apparently the Christian Golden Rule to “do unto others as you would have others do unto you” did not weigh on their consciences. So calling out England for a system the Southern Colonies had no intention of eliminating was just silly. They were also no doubt acutely aware of the growing anti-slavery movement in the Kingdom of Great Britain.7

Washington, according to folklore, could not tell a lie, but he was not above looking the other way. He privately made it known that he thought slavery should be abolished, but in a phased out approach, preferably after he was long gone.8

None of the 13 colonies at the time considered slave-owning illegal. It wasn’t as pronounced in the north for economic reasons mostly. The south’s economy was dependent on large crops such as tobacco and cotton that required large amounts of manual labor. The north was made up of smaller farms and trades, such as ship-building, metal-working, milling, and printing, and the maritime industries of fishing and whaling. Especially for the trades in the north, free labor was readily available in the form of indentured servitude, in which kids were sent to work without pay to learn a craft. After five or seven years, they might earn their freedom.

The “all men are created equal” clause in the Declaration is taught to students to mean all people, but that, of course, was not how the Founding Fathers meant it. They would later clarify this by establishing in the Constitution that black men were equal to three-fifths of a white man. It was no oversight that women were excluded altogether since married women at the time were considered the legal property of their husbands. Indigenous people were not considered at all and described as “savages.”

A little thought experiment

IMAGINE FOR A MOMENT that on that balmy day in July 1776 it was not just wealthy white men who congregated to “form a more perfect union.”9 What if, in a moment of true enlightenment, those distinguished 56 gentlemen sought the input of people such as Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), a Mohawk leader fluent in English who had actually held court with King George and who was a skilled negotiator among the Iroquois, colonialists and British. What if William Lee, Washington’s black valet and confidante, had been asked for his input? Or perhaps Prince Hall, a black soldier who joined the charge of Bunker Hill and was a leading advocate for the rights of his people?

Or what if Abigail Adams, a feminist ahead of her time, held an equal voice at the table alongside her husband John? How about if enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley, who challenged the stereotype of her people, had also been asked to speak?

What do you suppose the Declaration of Independence, and later the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, might have looked like had they been written by an assembly truly representative of all the people at the time?

Of course, we can only speculate. But we can do more than that when we scrutinize the output of the 56 men who were there. They were certainly successful in laying the groundwork for freeing the fledgling nation from a far-away monarchy. But the system they put into place was, when viewed from a truly objective perspective, not altogether that different.

Meet the new boss, same as the old boss

TODAY, CITIZENS ARE MARCHING in the street chanting “No Kings,” which is a proxy for “We’re not going back to an autocracy.” But, ironically, King George III’s powers back then were limited. The British already had a parliamentary form of government. It was that legislative body that voted to pass onerous laws on taxation in the states, that managed the states’ trade with England, that held the “power of the purse,” controlling spending for all the government’s affairs, including the military. They also collectively decided the governors of each state.

And even though the king was the recipient of the Declaration, there was a strong sentiment among the Founding Fathers that it was parliament, not the king, that had overstepped its authoritative line. The original idea for revolting was to circumvent that British legislature and remain loyal to the king, essentially just cutting out the “middle man.” Franklin was an early proponent of this strategy. 10

Moreover, monarchies were beginning their final chapter in Europe. The Western World was rapidly moving to a political-economic system based on capitalism, where money, rather than bloodline and inheritance, equaled power. It was the new system taking over the old, a system that required insatiable growth through the exploitation of “new” lands and the occupants therein.

The name of the socio-economic model got re-branded from parliamentary monarchy to democracy, but it was pretty much the same thing. And the result was the same as well: One colonizing empire swapped out for another. It was still rich white men running the world, co-mingling their personal financial interests with the public’s interest. If you write the rules for the game of government, and can change the rules whenever you want, you will always win. Money buys power and power is the root of all evil, especially in politics.

That is why the type of “equality” laid out in the Declaration holds pretty true today, where 63% of U.S. senators are white men, despite being only 29% of the population, where more than half of all Congressional members are millionaires. Today, 30% of the wealth in the U.S. is concentrated in the hands of 1 percent of the population, of which 90 percent are white and mostly male. And these are the people that pour obscene billions into lobbies and elections to get what they want. And when they get what they want, they want more.

The Founding Fathers undoubtedly considered their work to be sowing the seeds of democracy, but what they actually planted was the root of unfettered capitalism, a root that took hold and propagated like an invasive species, one that is all but impossible to weed out today.

All of this is to say that the Founding Fathers’ dream came true, just not the way it is taught in elementary school.

FOOTNOTES

- The 13 original colonies were: Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia. ↩︎

- Franklin started his career at the age of 12, assigned to a 9-year indentured-servitude contract as a printer’s apprentice, under the ownership of his own brother. ↩︎

- To Hemming’s credit, while in Paris, where slavery was illegal, she negotiated with Jefferson that she would only return to the United States in exchange for extraordinary privileges compared to the other slaves at the time. Jefferson conceded. She went on to bear four of his children. SOURCE: Monticello.org. ↩︎

- Source: Peter Stark, Sins of the Founding Fathers ↩︎

- The actual size of the combined estate of Martha and George Washington is a bit difficult to ascertain, since her fortune was tied to her previous husband. George Washington took control of those affairs, but could not legally own them outright. Nonetheless, his wealth increased about tenfold as a result of their marriage. ↩︎

- This grievance is generally interpreted to mean a complaint in which soldiers had the right to sleep in civilian homes. But U.S. marines in tents in California cities at the time of this writing has an equally threatening effect. ↩︎

- Slavery would be abolished in the British Empire in 1833, although one could argue that it survived in other forms of involuntary servitude. ↩︎

- In his will, Washington stated that all his slaves should be freed after Martha’s death. But Martha decided to free them immediately after George’s death, because she feared the slaves might simply kill her to obtain their freedom. Source: mountvernon.org. ↩︎

- This is written in the preamble to the U.S. Constitution of 1787. ↩︎

- The Royalist Revolution, Monarchy and the American Founding, by Eric Nelson. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.