In France, the ringing is incessant

SHOULD YOU DESIRE to escape the din of daily life and decompress by soaking up the local culture of a quaint, quiet village or town in France, here’s a pro tip: Stay away from churches.

To be clear, I’m not advising you against visiting or patronizing a place of religious worship. But if you enjoy sleeping in on vacation, beware that these houses of the holy contain bell towers, or what can easily be described as the world’s largest alarm clocks.

Ste. Thérèse ringing out in Rennes, France

As a seasoned traveler who is also a light sleeper, I have an exhaustive list of places to avoid when securing lodging: busy streets and intersections, hospitals, fire departments, sports stadiums, bars and clubs. But until now, “church bells” was not on the list.

In France, there are somewhere around 45,000 places of worship, most of them of the Catholic persuasion. The overwhelming majority of these temples possess a lofty tower where a hefty tube of cast bronze is suspended. And when that metal-alloy cylinder is struck with what is known as a clapper, the reverberation can be heard and the resonance felt for great distances.

Moreover, the knell of the bell is not a rare event. Every occasion seems to warrant a clanging. They chime to announce the hour. They toll vigorously to recruit parishioners for services, of which there are many throughout the week, especially on Sunday. They peal excitedly for what seems hours on end to honor a multitude of saints on the days of their birth or their martyrdom.1

On the town

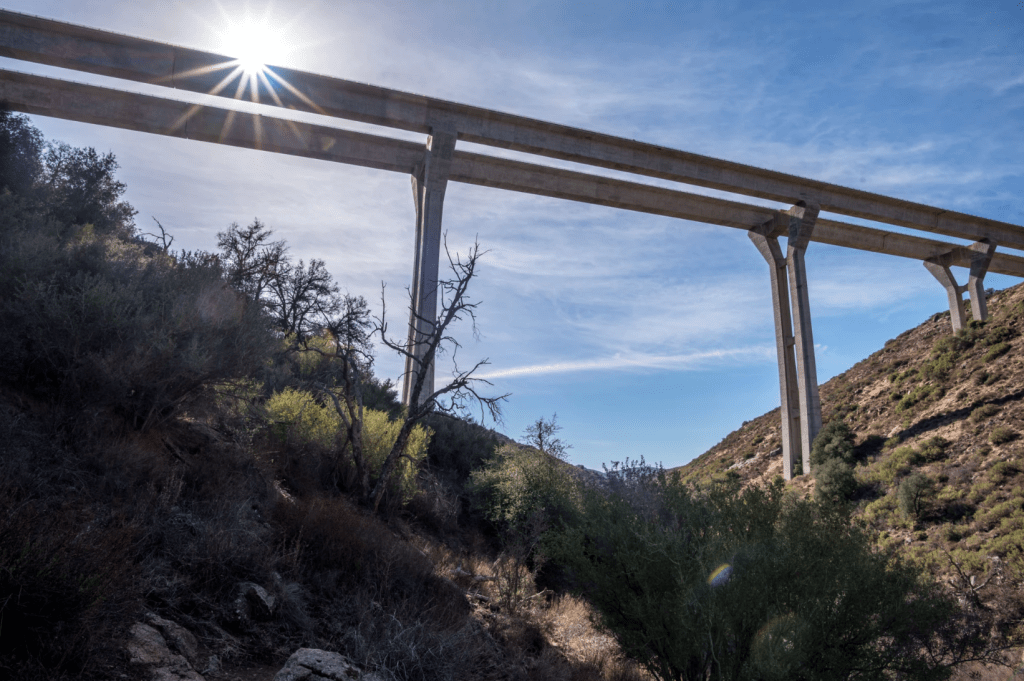

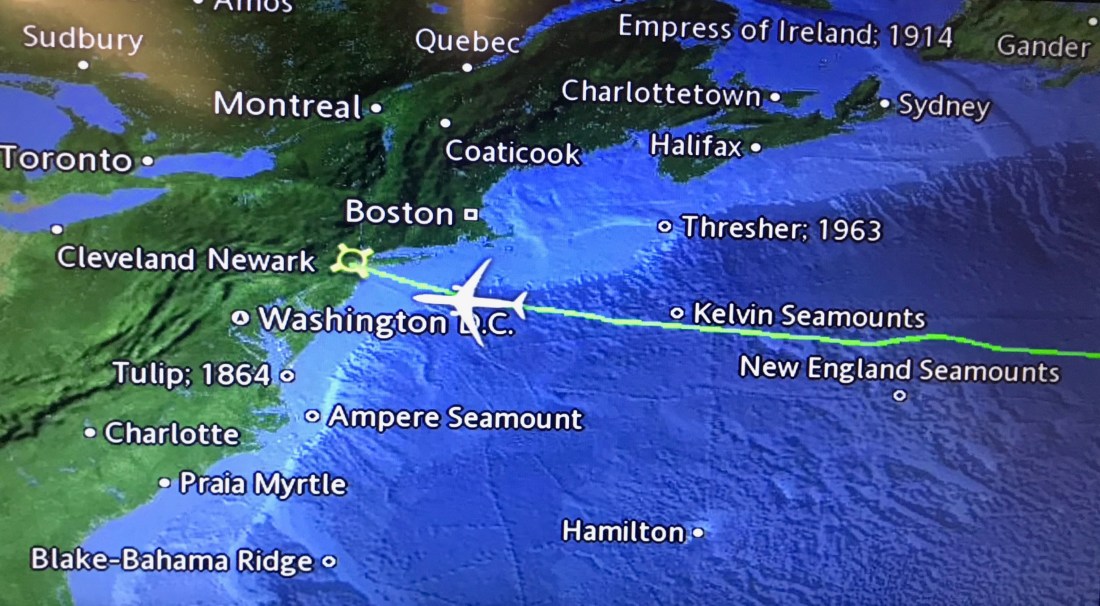

WE ARE TEMPORARILY residing in the city of Rennes, France, situated at the confluence of the Ille and Vilaine rivers, which drain into the Bay of Biscay and the Atlantic Ocean some 100 Km to the southwest. The weather here is mild, often overcast and sometimes rainy, as is typical of a coastal town.

Ste. Thérèse

This city is the administrative capital or prefecture of Brittany. And although Rennes boasts a population of nearly 750,000 in the greater metropolis, it’s really more of an aggregation of tiny villages and neighborhoods, many with the requisite cobblestone streets, provincial-style residences and small shops (which seem to be closed most of the time). There are also many modern apartment buildings and offices. This city even has a subway system. But in general, the place feels unhurried, relaxed, low-key.

In our little quiet neighborhood, we may hear magpies, crows, seagulls, pigeons and an occasional backyard dog voicing objection to its aerial companions. Cars, trains and the usual hub-bub of city life are barely audible. We rarely detect jets overhead, even though there is a regional airport just six or so kilometers away.

And then this serenity is interrupted by the ding-donging.

We are across the street from the Eglise de Sainte Thérèse, an impressive neo-Gothic structure built about 100 years ago. They spared no expense on the bell towers. And whatever that cost was, they have gotten their money’s worth. From 8 a.m. until 8 p.m., they ring on the hour. (Occasionally, however, someone might lose count. )

For religious services, there is a preamble — a warning of sorts — of three sets of three rings. And then, after a brief interlude, all hell’s bells break loose. This carillon2 cacophony may endure for ten or fifteen minutes. For the musicians reading this, I detect four tones: 1. The tonic, 2. A major second, 3. A major third, 4. An octave. If you remember singing class in school, this would be DO-RE-MI-DO.

Every neighborhood has its own church with its own bell tower. Because the terrain is flat, the sound carries unimpeded. Frequently, not just one, but as many as three or four churches nearby compete for attention with Sainte Thérèse.

All this chiming got me to thinking how this tradition got started and, perhaps more to the point, why this anachronism persists.

Hear ye, hear ye

LOUD SOUNDS HAVE BEEN used to communicate for just about as long as humans have been assembling in social groups. Whether its a conch shell or a drum, any reverberation that can carry for long distances has been used to convey a warning (enemy is approaching), or perhaps an invitation (festival tonight to celebrate the solstice).

Once organized religion became commonplace, trumpets, gongs and other such instruments were used to invite the masses to, well, Mass. It wasn’t until 604 A.D. that a Pope Sabinian sanctioned bells as the most effective method of communication.3 And the rest, as they say, is history.

Marco Lachmann-Anke

The question, though, is why continue? In this day and age, we certainly don’t need any reminder of the time of day. And, let’s face it, the bell-ringers are not going to be as accurate as a smartphone clock, which is synchronized over the air with an atomic timekeeper (located in some secret bunker in the Colorado mountains) right down to the millisecond.

As for the announcements of religious services, wouldn’t a group text be more effective? (Add a link to a Patreon page to skip the fund-raising basket that’s passed from pew to pew during services.)

In fact, all this ringing can unequivocally be defined as noise pollution. Studies in Switzerland and the Netherlands have concluded just this. But tradition is strong here in the land of the Gauls, and it is unlikely the musical tones emanating loudly and clearly through villages, towns and cities will be silenced by some silly, modern notion of what constitutes clangour.4

So I, consequently, have developed my own tradition to cope when the boisterous bells erupt, which is to mutter under my breath: “Off with their heads!”

FOOTNOTES

- France boasts 1,376 Catholic saints, of which 656 died as martyrs. ↩︎

- Carillon is derived from Old French quarregnon, which means the peal of four bells. ↩︎

- Pope Sabinian was only in charge for two years, but he certainly achieved a rather notorious kind of immortality with his bell-ringing decision. ↩︎

- Clangour is defined as a loud non-musical noise made by a banging or ringing sound. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.