The Tesla brand is in meltdown and the moral of the story is worthy of an Aesop fable

LET ME TELL YOU A TALE and it’s a good one. It’s about a Boy Genius who came to a place known as the Land of Opportunity and thanks to his privileged heritage he rose quickly to a prominent position and was then able to convince the Smart People of the Land of Opportunity that he was going to create a new kind of car that could help humanity and at no extra charge save the entire world. He built the car and he sold many of them, because the Smart People really, really believed in his vision and the cars were pretty sporty.

thanks to Elon Musk’s inability to understand

the Golden Rule of Business: Know Thy Customer.

He had the Midas touch.

He then erected and launched rockets and said, “Saving Earth is cool and all but why not invade some other planets? That would be cooler.” And the Smart People thought, “Well, he did build that car. And now these rockets. He is superhuman. We should listen to him some more.” And they did. And he became the richest Boy Genius in the world.

And then things got weird, or rather the Boy Genius got weird. Very weird. He became addicted to his power, fame and fortune and many, many pharmaceuticals. And then he not only joined but became a leading proponent of the Vile Movement.

The Vile Movement was everything the Smart People did not like. This made it clear to the Smart People that the Boy Genius didn’t mean any of that stuff about saving the world or helping anybody but himself. All he was doing was using the money that he got from the Smart People to finance causes that would destroy everything they believed in.

And that’s when his Midas touch backfired. That’s when he realized he could not eat his gold. You see, these Smart People became very angry. Many unloaded their cars. Some plastered bumper stickers making it clear they hated this Boy Genius despite owning the car. Protestors took to the streets. His company went into what the Boy Genius might describe as a “rapid unscheduled disassembly.” That’s a nice way of saying it imploded.

The Boy Genius earnestly and without a hint of irony asked: “Why are people so mean?” And then he announced that he would get back to making stuff, really cool stuff that nobody but he — the Boy Genius — could make. But the Smart People who bought his cars and had supported his vision didn’t believe him anymore, because the Smart People now realized he was not a genius, he was just a boy like the one who craved attention so badly he cried “wolf” too many times. The Boy Genius was just someone who could never be trusted again.

Will the Boy Genius rise from the ashes like Phoenix or better yet save his own company like Steve Jobs?1

Stay tuned for next week’s episode!

To be honest, no one knows just yet, so don’t expect a subsequent installment. But I do think I know what the moral of the story is and it is worthy of an Aesop fable.

I bought the vision with U.S. dollars

I MIGHT AS WELL ADMIT IT it right up front: I was sold the first time I rode in a Tesla. It was 2014 and a colleague of mine offered a ride to some meeting in San Francisco. As he hit the pedal, the torque threw my head into the headrest. It was exhilarating. We zipped through traffic on 101 North as he regaled me with stories about over-the-air updates. “It’s just an iPhone with wheels,” he said, as the autopilot app merged us into the left lane.

It was cool. It was unlike anything else on the road. And it was a unique approach to using renewable energy. A luxury vehicle that rode you around in style and saved the environment. What’s not to like?

At the time of this little excursion, I had spent just over 20 years in Silicon Valley. And, to be honest, I was jaded. I had seen lots of technologies come and go. The pattern was abundantly clear to me: A New Shiny Thing appeared and promised to disrupt some big bad legacy industry and in the process the New Shiny Thing would make the world a better place for all.

That was the promise of the World Wide Web, social media, business intelligence, the cloud, you name it. All we got out of it was the likes of Google, Facebook, and Amazon scraping our private data and harnessing our very personal proclivities for fun and profit.

Tesla checked all the boxes to qualify as the New Shiny Thing and then some. It wasn’t just disrupting the auto industry, it was upending the entire power grid as well by creating a new model for the production and consumption of renewable energy.

I watched with amusement as auto execs scrambled to join the EV parade and as the PG&Es and ConEds of the world struggled to adapt their monopolies to a distributed energy network that they couldn’t control.

All of that was impressive. But what really sold me was the Tesla mission statement to transition the world to renewable energy. It was based on a manifesto supposedly written by Elon Musk himself.

is real for many Tesla owners.

And so that glimmering, shimmering object, that silvery emblem with a “T” was the lure that caught my eye. And despite my experience-based cynicism, this time I bit: hook, line and sinker.

I even chuckled to myself that I had missed a golden opportunity with Musk years before.

A kid named Elon who wasn’t kidding

HE WAS JUST ANOTHER 20-something nerd, one with a prematurely receding hairline and a latent outbreak of acne, when I met him in 1996. He had called me up and asked for a meeting. At the time, I was running the Java Developer Ecosystem at Sun Microsystems. My voice mail and email were clogged with similar requests because Java, a programming language invented by James Gosling, was fortuitously just the right platform for Internet-based applications. Java was red hot. Every start-up in a garage had an idea for the next big thing using Java.

But Musk was quite persistent and so I did meet with him, and his brother — Gimbel, Gumball or something like that. It has come to light recently that the two Musk boys had overstayed their visas in the United States around this time. So, apparently, I bought breakfast for two illegal aliens and then listened to their pitch. (Please do not tell ICE.)

Elon did all the talking. His patter was fast and his Afrikaans accent was thick. All I could glean from his running monolog was that he wanted to sell his company, called Zip2. Naturally, I assumed the enterprise had something to do with replacing snail mail with email, which had already been done. But it turns out Zip2 was even more boring: It was just online classified ads. And he never once mentioned how Java fit in. So I passed on the opportunity.

But now, here he was, 18 years later in 2014, proving me wrong. He had sold Zip2 for a tidy sum, started another company that got acquired by PayPal, which then got gobbled up by eBay. He cashed out and funneled those funds into Tesla, where he financially elbowed his way into the CEO position. He turned out to be the Boy Genius after all. I wondered how I could have gotten him so wrong.

Shortly thereafter in 2015, I had the chance to meet J.B. Straubel, one of the founders of Tesla. That’s when I learned who was the technical mastermind behind much of the company’s technology and operations. It was Straubel who invented the battery cell design that was the breakthrough for electric vehicles, giving them the range of gas-powered cars.

Straubel was the guy behind new manufacturing processes, including the Gigafactory. And he created a whole new market with another idea: the PowerWall.

The anti-Musk movement is worldwide.

So, I thought, Musk was the prancing show horse, Straubel the diligent — but brilliant — work horse. This was not an uncommon arrangement in Silicon Valley. Behind every Steve Jobs, usually there was a Steve Wozniak. This just reinforced my appreciation for what Tesla was doing.

In the following months, I wrote several positive pieces about the company in my blog and in CIO magazine. And then, starting in 2017, I went fan boy. I ended up buying the whole package: First the solar panels, then a Tesla Model 3 Long Range, then the Powerwall II. I signed up for Starlink beta as soon as it was available. I bought Tesla stock.

Today, I own none of those things. And I am just one of perhaps hundreds of thousands of formerly loyal customers who have shed all their Tesla assets in direct protest against Musk.

He never saw it coming, and still doesn’t understand why

HONESTLY, I WAS AS SURPRISED as many other FTOs — Former Tesla Owners — at how quickly the anti-Musk movement achieved its formidable momentum. That surprise was not without a tinge of schadenfreude.

But, I am reasonably sure, no one was more shocked than Musk himself. I think I know why there was such animosity from the FTOs toward Musk, and why he can’t comprehend what is happening.

What Musk — who believes that empathy is a weakness — either forgot or never learned was the Golden Rule of Business:

Know Thy Customer

I’m going to profile the Tesla buyer, of which I was one. We are mostly Baby Boomers and Gen-Xers with a decent chunk of disposable income. We are educated and liberal. We are technically savvy. We voted for Hillary even though Bernie was the better choice. We voted for Kamala even though we are inspired by AOC.

We take climate change seriously.

We advocate for equal rights for all people, regardless of ethnicity, color, sexual orientation or religious beliefs.

We make fact-based decisions. We trust science.

We started Earth Day. We lobbied worldwide for fixing the ozone and it worked. We bought into recycling, organic foods, renewable energy, hybrids. Some of us were hippies, and then yuppies. We abandoned organized religion and leaned into New Age with Buddhism and meditation. And then we became parents and then grandparents who only want a better place for our kids and grandkids.

The anti-Musk vitriol being expressed now reminds me of another story, this one from Aesop, titled “The Farmer and the Viper.”

A farmer finds a viper outside in the freezing cold and decides to be kind to the animal, so he takes it inside. After the viper warms up, the snake bites the farmer.

Moral of the story: Don’t be kind to Evil.

Tesla buyers, at the risk of stating the obvious, are the farmer in this fable. We thought we were doing the right thing helping the viper. But we learned our lesson. We have banished the viper from the house because we absolutely do not want to be kind to Evil.

Once bitten, never again

SO WHEN MUSK WENT FULL-ON MAGA and entered Washington D.C. with a chainsaw, this is the nucleus of the population that collectively lost it. This guy was supposed to be our salvation. Instead, he sold us down the road.

What made it all the more aggravating was that there was considerable merit in what Tesla the company was doing; thank you J.B. Straubel.

This was not ENRON. In fact, it was even worse than being swindled by some fraudulent accounting scheme. We expended our hard-earned dollars not as just a financial investment but as an emotional one, supporting Musk to lead the cause. It made him obscenely rich. Now, here he was funneling our dollars into the very antithesis of what we believed in.

And we still want that better place, damn it.

Time to do some soul searching

BUT WHAT IS EVEN MORE TROUBLING for many of us, and I include myself in this group, is that we were duped in the same fashion as the Conservative Cult Crowd.

For 40-plus years, we have watched in disbelief as Republicans slipped into their dystopian mind-numbing coma, starting with Ronald Reagan, then George Bush aka Dick Cheney, and culminating with the Charlatan Clown. We wondered how it was possible voters could not see what was happening right in front of them. And, I might add, right to them.

Yet, we Tesla owners smugly assumed we were too wise to get conned, all while we were being led by the nose by a scam artist of our own making.

To be very clear, all the ideas about climate change and what’s needed to save the planet are valid, scientifically proven. But we should have been listening to Greta Thunberg, not Elon Musk. We should have been investing in mass transit, in urban planning, in shutting down the fossil fuel industry and reining in the Military Industrial Complex. Yes, Tesla has some interesting technology. But the environmental mission statement — the manifesto — is gone from Tesla’s website, and all we got were several million more cars clogging our already overburdened streets and highways. All we ended up with was another disappointing New Shiny Thing failing to live up to the hype.

And here is the trap that we all fall into, regardless of our ideology, political affiliation, religious beliefs. Once we’ve invested, we tend to want to double down to justify our actions. Throw some good money after the bad in a vain attempt to regain our original investment. We live in denial that we made a mistake. This is the sunken cost fallacy.

We knew about Musk’s true character long before January 2025. But we had already bought in.

He spouted disinformation about COVID and violated laws to keep his Fremont factory running at the height of the pandemic. But we looked the other way. He displayed his racist-misogynist views on Twitter and then bought the platform and turned it into his own crowd-sourced Elon Musk adoration society. We again gave him the benefit of the doubt.

Unsafe at any speed

YET, IT WASN’T JUST THE dangerous political views that we conveniently dismissed. Even more egregiously, we forgave the “safety idiosyncrasies” of the Tesla car’s overall road worthiness.

We knew that Ralph Nader and many others had been warning U.S. regulators about the inherent design flaws in Tesla’s automated system for years. We not only chose to ignore the warnings, we drove the damn vehicles. Since 2014, the National Transportation Safety Board has tracked hundreds of accidents and 51 fatalities involving Tesla’s guidance system. I can personally relate one incident while driving our car that came close to adding my spouse and me to those statistics.

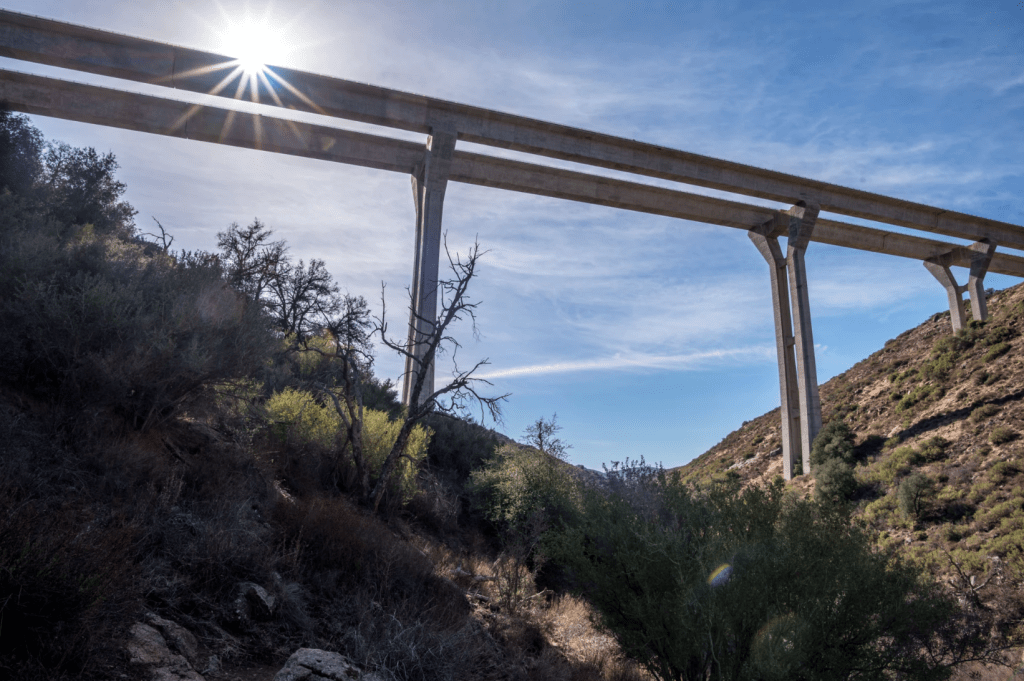

We were driving on I-5 north of Bakersfield, California on a clear day with perfect visibility. The road was straight. There was very light traffic. We were cruising along at 80 mph, using FSD (full self-driving). I was in the driver’s seat and I can attest that both my hands were on the wheel, when the system, without warning, slammed on the brakes.

The car skidded and swerved into the right lane before I regained control.

What caused this malfunction? This is known in the Tesla world as “phantom braking.” Whether there is a ghost in the machine or not, I don’t want it activating a “sudden unplanned deceleration” to a dead stop, especially when I’m moving almost 120 feet per second.

Here is my analysis of what happened:

There was nothing directly in front of us. But, about a quarter mile up the road, there were two white 18-wheelers side by side, as one overtook the other. My guess is the reflection of those two vehicles, which were just underneath a white concrete overpass, confused the Tesla cameras and software, which interpreted the three distinct white objects as one large obstruction. We were heading at high speed toward a giant wall, as far as the computer was concerned.

Even worse, the system misjudged the distance to this imaginary barrier as not a quarter-mile ahead, but directly in front of us. That is the only feasible explanation for why the car functioned the way it did.

This is a well-documented problem with Teslas. Musk insists the cars don’t need radar or LIDAR but obviously the cameras alone are not good enough as sensory input for full self-driving or any kind of assisted driving. Fortunately, there was no one behind us or in the right lane when this occurred, as has happened on the Bay Bridge and elsewhere.

That was the scariest incident, but not the only one for us. The car easily got confused whenever roads had been widened or repaved and residue from the old white lines remained faintly visible, or when there were traffic cones or other temporary modifications to the surface or surroundings. The car would swerve and brake without warning. We used FSD only a few times, and paid diligent attention whenever we had it activated. It never, ever felt safe.

Adding it all up

NOW IN RETROSPECT, as I think about it — the 180-degree change in politics, the disturbed behavior of the man both personally and professionally, the clearly dangerous condition of the cars — I feel like Homer Simpson, slapping my forehead. How could I have not seen it? I might as well have given $100,000 to that Nigerian prince. At least his emails were polite.

And here is the hardest realization to face: I can deride the MAGA crowd who believe in Jesus Christ and yet can justify voting for a convicted rapist and felon who doesn’t even know which end of the Bible is up (literally). Weren’t the other Tesla owners and I compartmentalizing our actions as well?

I didn’t think I could be that easily persuaded to look the other way. So I’m angry, not just at Musk, but at myself. And I bet the other FTOs (Former Tesla Owners) are feeling the same way.

How did this happen to a bunch of well-education, well-informed people?

The power of myth

THERE IS A SCHOOL OF THOUGHT, led by some serious thinkers such as Yuval Noah Harari and Karen Armstrong, that posits that there was one very key distinguishing characteristic that led to homo sapiens surviving and even thriving, while the Neanderthals, Denisovans and other species went extinct. It wasn’t our biology, superior tool making, or language. It was fiction: Telling ourselves stories that give meaning to things we don’t understand.

Where did we come from? Viracocha, or Brahma, or God. Take your pick.2 Why do we die? We don’t! We just go somewhere else in another form. Why was there a flood just when we were bringing in the crops? Oh, the gods must have been angry. Maybe we need to slaughter a lamb to appease them.

Myths are the easiest path for our minds to take to explain these intractable problems.

Once humans developed this line of thinking, some interesting behaviors appeared, because believing in a common set of myths can act as an organizing principle. If one person can convince the others that he or she has been designated to act as the messenger for a god or gods, it’s pretty easy to get those people to fall in line.

The Code of Hammurabi is considered one of the most important and influential ancient legal documents in the world. But the Babylonian king for which it is named did not profess to write the 282 laws himself. He was just the messenger, delivering this fiat directly from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice.

Moses and the Ten Commandments has a similar plot.

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson cites that …”all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights … ” Jefferson was just acting as the scribe for a divine being when listing those rights.

Humans conjured up religion, the concept of money and monetary systems, laws and moral codes. But by convincing ourselves these abstract notions were either handed down from on above or have some higher sense of purpose, we have a convenient way to create order out of chaos.

Oh, how we love a good story.

And this is how humans were able to organize in bands of not just 50 but 500, 5,000, even 5 million. It’s how you build pyramids (and pyramid schemes), how you wage crusades, how you get millions of people to put their hands on their hearts and tearfully pledge allegiance to a fictitious entity called a country.

You can motivate a heck of a lot of people to work in concert and accomplish some pretty crazy things just by convincing them they are parter of some bigger, mysterious force.

Neanderthals never saw us coming.

The Silicon Valley myth

SOMEWHERE ALONG THE WAY in the 1990s, when our generation elected the hip, saxophone-toting Bill Clinton to be the first Baby Boomer president, we thought that maybe, just maybe we could forge a different economic model, where capitalism meets altruism, where we could throw out all the old rules for business and society, thanks to microprocessors and software.

We sincerely believed that Silicon Valley ideas, fueled by a few million in venture capital dollars, could, like alchemy changing lead into gold, make the world a better place and if some people got rich cashing in their ISOs and NSOs3 in the process, well that was pretty cool, too.

Here’s what we really did: We created our own story. It’s the Silicon Valley Myth. Its a recipe made up of all the beliefs we already know and trust: You just add a slight twist of technology, a dash of religion, a sprig or two of Adam Smith, seasoned with Utopian philosophy. Sprinkle in some goofy company names to pretend work is fun, toss in some free meals and Pilates for good measure.

Many great things have come out of Silicon Valley. Many people got rich. But, let’s admit it, the business model is no different than the Industrial Revolution: Make things and services faster, cheaper and better.

In both eras, as technology rapidly changed the status quo, humans had trouble keeping up. Some, like the Luddites revolted. Today, maybe a similar trend is the anti-vaxxers. We get overwhelmed. We look for shortcuts to the answers.

And that’s when we elevate certain people we consider successful to that myth-like status of Moses and Hammurabi.

In the Gilded Age it was the likes of Rockefeller, Edison and Carnegie. In our times it is Steve Jobs4, Bill Gates, and yes, Elon Musk. Good story tellers all who conveniently fulfill what we ask of them: to pretend they are superhuman and have all the answers.

So when a Musk comes along and says “I’ve got the solution to climate change and it’s actually cool and fun!” we fall into the same trap as all those humans before us.

We love a good story.

So, it should be no surprise that Silicon Valley employees and residents were among the earliest of early adopters of Teslas. It was the story for all Silicon Valley stories.

Rise and shine!

BUT HERE IS WHERE I GIVE MYSELF and my fellow FTOs some credit. We woke up. Yeah, think about that: We’re WOKE. And us Woke Folk woke the fuck up. We have chased that viper out of our house and it shall be banished forever.

We took to the streets and pulled the road out from under Tesla at a very critical juncture in the company’s existence.

Tesla had already been falling behind. It’s cash cow Model 3s and Model Ys were outdated at a time when EVs were fast on their way to being commoditized. BYD can deliver a better vehicle at half the price. And they aren’t just copying, they are innovating. Meanwhile, Tesla’s newest offering, the Cybertruck, is an unmitigated flop, the 21st Century Edsel.

This is all happening just when Musk needs that Tesla revenue and profit to propel the next big plays for the survival of the company: robotics. Without that financial fuel, he is going to fall further behind investing in these highly competitive and potentially very lucrative new opportunities, at the very time he is losing the lower end of the car market.

This reminds me of another story, about the famous French wit Voltaire. On his deathbed, the prolific author was being administered the Last Rites by a Catholic priest, and the conversation went something like this:

Priest: “Do you denounce Satan?”

Voltaire: “No.”

Priest: “Why not?

Voltaire: “Now is not the time to be making enemies.”

Musk should have thought twice, even thrice, before biting the hand that carried him into a warm house, before pissing off the very customers he needed to move onto to the next big thing. It was the very wrong time to make enemies. But, of course, a viper does what is in its nature.

The only thing sustaining Tesla’s insane stock valuation now is Musk’s smoke-and-mirror show. Investors didn’t mind as long as the cash was rolling in. But the money is drying up, the smoke has dissipated and we see the man behind the curtain for who he really is. There is no path to winning back the hearts and minds of the FTOs any more than Bernie Madoff will arise from the grave and convince his old marks to invest in his latest Ponzi scheme.

I promise you this: I will never give Musk another dollar.

Musk — and Tesla — may survive, but he and the company inexorably linked with him will be forever tarnished, forever relegated to a case study in business school. It will be among the cautionary tales: Don’t do what these guys did. He will be right in there with John DeLorean of the eponymous car company, Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos, Inc., Kenneth Lay of Enron, and Adam Neumann from WeWork.

And to me, being in that company is the best place for Musk.

Unless he wants to go to Mars. I’ll break my promise and pay to send him to Mars.

FOOTNOTES

- Having met both Elon Musk and Steve Jobs, I can say with certainty he will never be Steve Jobs. Jobs asked questions. He was a diligent listener. Musk is in love with his own voice and ideas. ↩︎

- Virtually every organized religion in every culture has a remarkably similar story of the creation of humans. ↩︎

- ISOs: Incentive Stock Options, NSOs: Non-qualified stock options. These are “options” to buy a stock at a particular price, sometimes zero and then sell them at at market rate, almost always at a very healthy profit. Stock options drive much of the employee pay packages in Silicon Valley. ↩︎

- Steve Jobs died in 2011, but he is still among the top quoted and studied business gurus . ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.