We may think we’re Great, but, alas, we’re still Apes

ON A DRIVE FROM Yuma, Arizona to San Diego, California, I was captivated by the ever-changing, surreal topography. But two human-made structures punctuated the natural landscape in a way that got me to thinking about how much our species has in common with baboons.

Yes, baboons. But first, a bit about the scenery.

in the Arizona desert.

On Interstate 8, it seems the moment you traverse the border at the Colorado River, the saguaro cacti disappear. It’s as though these succulents, with their iconic outstretched arms reaching for the sky, are a proprietary brand of the Copper State.

Not to be outdone, the Golden State immediately presents you with the quintessential sand dunes of the Colorado Desert, sculpted by the wind into smooth giant hills, resembling mounds of poured sugar. Except for the occasional Joshua tree, yucca plant, or creosote bush struggling to survive, the dreamy-yet-desolate terrain seems right out of Lawrence of Arabia. You might expect to see the titular character bouncing astride a loping camel, kicking sand in the air with its hooves. The distant silhouette of the Chocolate Mountains adds to the backdrop, as though painted on a movie-set canvas.

It is just past the dunes that I-8 veers directly south and then hugs the international border with Mexico. It is here that you will be introduced to The Wall.

Structure No. 1: The Wall

DEVOID OF EVEN A SEMBLANCE OF AESTHETICS, the giant black fence of solid steel thrusts discordantly out of the terrain. To put it in today’s lingo: the wall is photobombing the vast, arid landscape. The Wall serves its utilitarian purpose, but with mixed results, as has been true of such barricades for millennia. Its xenophobic ancestry can be traced to the Great Wall of China, Hadrian’s Wall, and in more modern times, the Berlin Wall.

Ineffective though it may be, The Wall’s brutalist design sends an unambiguous political message: KEEP OUT.

Continuing west on I-8, the next section of The Wall you will spot is in the diminutive town of Jacumba Hot Springs. This hamlet of 800 or so souls has the privilege of sporting one of the first incarnations of this ugly fortification, erected during the Clinton administration.

I’m not sure who had the bright idea to construct this monstrosity with steel plates left over from the Vietnam War. Maybe some political consultant thought this could be spun as a “swords to plowshares” narrative.

But the irony is just too delectable to ignore. After using this material to violently (and unsuccessfully) invade a far-off land, all in the name of democracy, the U.S. then recycles this war-machine detritus to “protect” itself from huddled masses yearning to be free… Give me your tired, your poor,1 but not if they are your next-door neighbors, I guess.

All of this is worthy of a treatise on its own, but I’ll have to save that for a later day.

Although the wall in Jacumba is technically on the edge of town, it’s perceived by the villagers as having cleaved their lives in two, since many residents had or still have relatives in the sister pueblo of Ejido Jacumé on the Mexican side. What was once a casual 10- or 15-minute walk can now take a half day of driving — via the nearest “official” border crossing.

There’s plenty more diverse scenery to savor on this leg of the journey, including the Anza Borrego Desert and the Jacumba Wilderness itself. Also worthy of note is Smuggler’s Gulch, named in the 1880s for the cattle rustling that occurred between the U.S. and Mexico — in which direction I’m not sure. Here, in a very narrow canyon, giant sandstone boulders, many the size of a McMansion, teeter on cliffs. These car-crushing rocks appear ready to roll any minute.

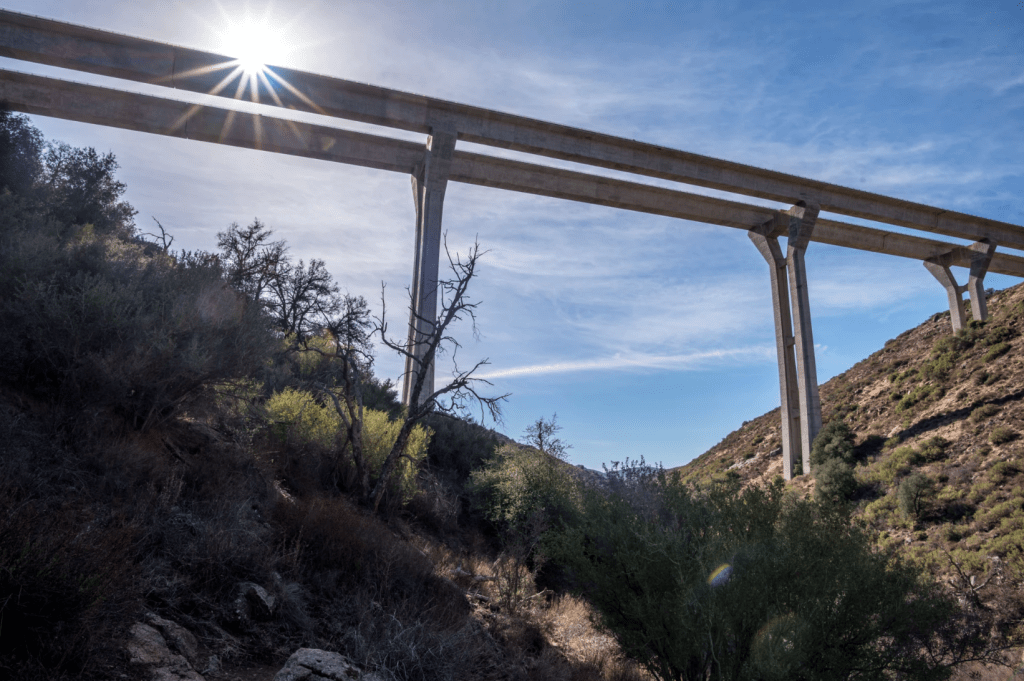

Structure No. 2: The Bridge

rises some 440 feet, or 134 meters, from the ground.

Photo by George J. Janczyn. Used with permission2.

AS YOU CONTINUE YOUR JOURNEY to San Diego, you’ll ascend once again and eventually enter the Cleveland National Forest. You will then be confronted with a deep canyon that would be impossible to traverse in any vehicular manner were it not for a unique marvel of engineering.

This is the second of the two aforementioned structures that brought baboons to mind (yes, I’m getting to that). And it is officially known as the Nello Irwin Greer Memorial Bridge, named in honor of the engineer who managed the project. But it is more commonly referred to as the Pine Valley Creek Bridge.

Now — full disclosure — I’m a bit biased when it comes to comparing walls to bridges3. The former is there to exclude one group of humans from another. The latter, on the other hand, intends to unite us.

At the time of its completion in 1974, the Stone Valley Creek Bridge was the highest concrete girder viaduct in the world. That is impressive. But for me, what is even more inspiring is how Greer and his team accomplished this feat utilizing such an elegant design.

The segmented cantilevered method used to hold the road bed aloft is a clever Y-shaped row of pillars. Moreover, the entire ensemble seems to at once blend in with its environs and enhance the scenery at the same time.

I can’t think of many “man-made” structures that can do that.

The backstory on this span across Stony Creek is a fitting juxtaposition to The Wall in Jacumba. Greer rerouted I-8 to save the town of Pine Valley, for which I’m sure its citizens are forever grateful.

The Wall cuts a town in two; The Bridge saves a town. You can see where this is all heading and that is why it is now time to cue the baboons.

EQ vs. IQ

I CAN’T SAY I HAD EVER HAD even a modicum of interest in learning about these distant primate cousins of ours until 2019. At the time, Sherry and I were hiking in the Table Mountain National Park at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa.

Although the Cape feels like the edge of the world, this walk did not seem particularly remote. There’s plenty of fellow tourists and the trail is clearly marked. There is even a restaurant at the summit.

in South Africa

But to our surprise that day, a mother baboon with a child in tow casually crossed our path and then nonchalantly sat on a wall, seemingly oblivious to our existence. We stopped for a while to grab a video but kept our distance, out of respect.

I was inspired by that incident to read up on baboons and came across A Primate’s Memoir, by renowned primatologist Robert Sapolsky, who had spent decades living among and studying these animals in eastern Africa.

To look at them, you’d notice very few physical characteristic similar to homo sapiens. Baboons walk on all fours, have a snout that seems to be a cross between a dog and a bear, and possess enormous, menacing canines just for good measure. They have tails and sleep in trees.

And to be sure, baboons do not make things, like walls and bridges. So what do we have in common?

Baboons are very social creatures, notes Sapulsky. They live in groups ranging from a few to fifty. They “work” a four-hour day, which is all the time they need to forage for food. They sleep another 10 hours. And that provides them with a full 10 hours to interact with one another.

And interact they do. They make friends; they make enemies. They establish hierarchy that can be inherited. If you are the offspring of the alpha male, you have it made. There are prom kings and queens, and wallflowers. They woo, they mate, they raise their offspring.

They can be snobby. They might bully. They can be empathetic. They can plot and form alliances to outmaneuver rivals. They seek revenge, often very viciously. They are not above kidnapping.4

Sounds a lot like a Netflix eight-episode dramatic series. It should not be surprising, then, that baboons seem to reflect so much of human behavior, since we still share 94% of the same DNA.5

We have certainly progressed intellectually far beyond the capacity of any of our ancient ancestors. We have self-awareness, sophisticated language, arts and sciences. We build not only walls and bridges but amazing technology. But let’s face it: our emotional intelligence, or EQ in modern parlance, hasn’t evolved at the same pace. That stuff has gotta be buried very deep in that 94% DNA we have in common.

As the old saying goes, we’re just apes with nukes. And that’s never been truer — or a scarier thought — than it is today.

Curiosity, the cat, and the Doomsday Clock

FROM THE MOMENT OUR ANCESTORS descended from the trees, we have been testing the law of unintended consequences. We discovered fire, brought it into our caves, where, along with warming our hands, we inhaled smoke and developed lung cancer. We hunted megafauna to extinction. We created factories and vehicles that burn fossil fuels that are cooking our planet, which, by the way, is our one and only ride through space.6

The list of things we have tried that have backfired is seemingly endless.

The Wall hasn’t stopped people from attempting to cross the border. It has, however, created a thriving underground economy — literally. Tunneling under the wall is a big business. And coyotes — guides who charge a fee to smuggle people across the border — are making money, sometimes simply scamming destitute El Norte-bound travelers out of their last pesos.

For the most part, we’ve tested this law of unintended consequences in the physical world. We more or less understand this tangible realm. We can sense it. We can feel it. We can grasp it not only intellectually but emotionally.

But the virtual world is different. Whereas in the physical world, the intended purpose of a bridge is obviously distinct from a wall, in the virtual world, things get blurry in a hurry.

In the 1990s I was working in Silicon Valley at the very infancy of the Internet. In those days, the buzz phrase du jour was “democratization of information.” Everyone would have an equal voice and be able to project that voice to the world. That bridge quickly became a wall when corporate interests privatized the internet, rewarding our worst instincts to drive their ad-based revenue models. And that’s where our baboon behavior just became amplified. Bullying, hate crimes, tribalism.

Emotionally, we just can’t keep up. Technology is advancing at a logarithmic pace, but the areas of the human brain that deal with emotion — the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, limbic system, hippocampus — continue to evolve linearly at, well, a snail’s pace.

In the brave new world, the scale at which our endeavors are likely to backfire is exponential.

With Artificial Intelligence (AI), we are being promised new and greater opportunities without any idea of what the scope of the consequences will be. It reminds me of the story about the moment just before the first test of an atomic weapon, when Enrico Fermi mused that there was a greater-than-zero chance the explosion would ignite the entire world’s atmosphere. 7

And yet, we did it anyway.

Curiosity may have killed the cat, but humans somehow keep on ticking.

Yes, we have somehow survived — so far. But there’s something else ticking, coming from the Doomsday Clock, which is now at a mere 89 seconds before midnight, its most dire setting since the metaphorical instrument was created in 1947. To put this into perspective, the clock stood at 7 minutes during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Eighty-nine seconds before midnight. Will you look at the time? It’s getting late. And on that note, sleep tight.

.

FOOTNOTES

- Paraphrased from the poem, The Collosus, by Emma Lazarus. The poem is inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty. ↩︎

- Creative Commons License 4.0. ↩︎

- My reverence for bridges was further instilled by my father, a civil engineer who designed and oversaw construction of numerous spans in his career. I remember as a child driving to Long Island and crossing the newly opened Verazzanno-Narrows in 1965, then the longest suspension bridge in the world,3 as dear old Dad regaled his offspring with myriad facts about the engineering marvel holding our rattling little Rambler station wagon some 228 feet (70 meters) above the water. ↩︎

- Sapulsky cautions against anthropomorphism, using terms such as kidnapping to describe baboon behavior. ↩︎

- Even higher with chimpanzees: 96%. ↩︎

- Humans would not survive the massive doses of radiation they would sustain in a journey to Mars. The proposals by megabillionaire oligarchs to inhabit other planets is pure folly with today’s technology. ↩︎

- Fermi jokingly offered to take bets, but it’s hard to imagine anyone wagering that such a catastrophe would occur, because if it did, collecting one’s payout in a planet engulfed in flames might be a tad difficult. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.